Breeding programme

After the discovery of the live Lord Howe Island stick insects on Ball’s Pyramid in 2001, it was decided to establish a conservation breeding programme for the species. Over the years, a total of five specimens were collected from the sea stack. Thanks to the dedication and immense efforts of conservation teams working to ensure their survival, their numbers have now grown to more than a thousand.

Melbourne Zoo invertebrate keeper Rohan Cleave in the zoo’s Lord Howe Island stick insect breeding facility. Photo: Jo Howell, Zoos Victoria

Melbourne Zoo invertebrate keeper Rohan Cleave in the zoo’s Lord Howe Island stick insect breeding facility. Photo: Jo Howell, Zoos Victoria

The administrative process regarding the export of live specimens dragged on for two years, meaning the backup population on the mainland could only be established in 2003. This was a precaution, since it was uncertain how many stick insects remained on Ball’s Pyramid and whether removing specimens for the breeding programme would not fatally impact the existing population. On the other hand, it was confirmed that the stick insects did not inhabit any of the islets around Lord Howe Island. The population on Ball’s Pyramid faced a high risk of extinction due to random events, such as extreme weather, rockfalls, or soil erosion.

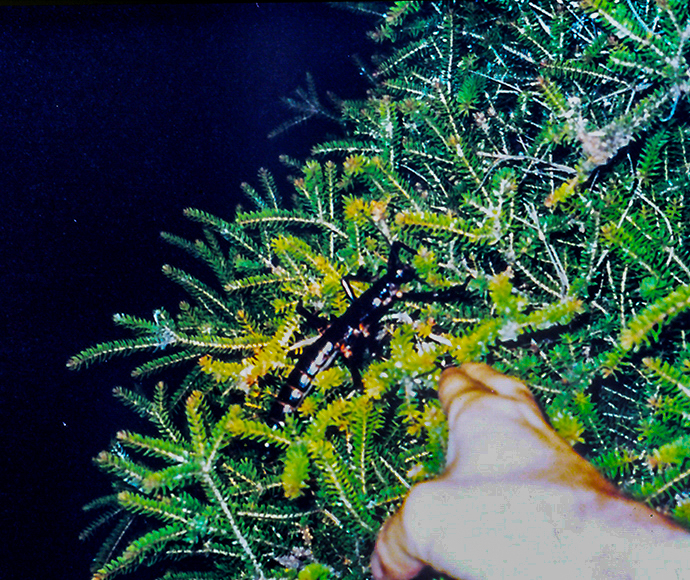

Depicting the first live Lord Howe Island stick insect discovered on Ball’s Pyramid, this photograph was taken by Nicholas Carlile during an extremely dangerous night-time ascent to the cliff edge where the tea tree bushes grew. He undertook the climb with Dean Hiscox, while the rest of the expedition spent the night at the base camp. Photo: Nicholas Carlile. Source: Return of the Phasmid, R. Wilkinson.

The first phasmids

During a follow-up visit to Ball’s Pyramid in March 2002, rangers discovered 24 live insects and were able to determine the sex of ten of them: eight females and two males. This was good news, as only females had been found the previous year, and it was uncertain whether any males had survived at all—female Lord Howe Island stick insects are capable of parthenogenetic reproduction. Based on this discovery, approval was granted to collect not just two specimens, as originally planned, but two pairs. After extensive preparations, these were successfully retrieved from Ball’s Pyramid during the night of 12–13 February 2003 and then transported in specially designed tubes to two carefully selected and prepared breeding facilities.

A special hinged tube lined with soft fabric was created to transport the Lord Howe Island stick insects from Ball’s Pyramid to breeding facilities. Photo: Patrick Honan. Source: Return of the Phasmid, R. Wilkinson.

The foundations of captive breeding

One pair of Lord Howe Island stick insects was entrusted to an experienced private breeder in Sydney, Stephen Fellenberg, who had participated in the original 2001 expedition to Ball’s Pyramid, where the supposedly extinct species was rediscovered. During the first two weeks in captivity, the female laid 21 eggs. However, 29 days after the acquisition of the breeding pair, the male died, followed by the female the next day. It was a major setback, but relief came when eight healthy nymphs hatched from the eggs.

Stephen Fellenberg, founder of the Sydney breeding, during the 2001 expedition to Ball’s Pyramid. Photo: Nicholas Carlile. Source: Return of the Phasmid, R. Wilkinson.

The other pair was sent to Melbourne Zoo, which had a strong focus on entomology, including research and breeding. The head of the zoo’s Invertebrates Department, Patrick Honan, named them Adam and Eve. From the very beginning, he experienced some tense moments: it seemed Eve might not survive. However, through great effort, Honan managed to save her and establish a thriving breeding programme. In the end, Eve lived for 15 months in captivity, laying approximately 250 eggs, from which 71 offspring hatched. Adam lived three months longer.

Photographs from the conservation breeding programme in Melbourne. On the left, Patrick Honan captured Adam and Eve mating under red light, which does not disturb this nocturnal insect. On the right is an X-ray of Eve with eggs, taken as part of the effort to determine the cause of her health issues during the first days after her transfer from Ball’s Pyramid to Melbourne. Photo: Patrick Honan. Source: Return of the Phasmid, R. Wilkinson.

Fittingly, the first nymph at Melbourne Zoo hatched on 7 September 2003—Australia’s National Threatened Species Day, marking the death of the last Tasmanian tiger. The nymph was named Yarra, an Aboriginal word for "stick". Initial success was, however, soon followed by difficulties. The eggs being laid became progressively smaller, and both the hatching rate and nymph survival rate declined, likely due to inbreeding caused by the small number of founders. To address this, in June 2004, four males from Melbourne Zoo (including Adam, making him the most well-travelled member of his species) were exchanged for four different males from Sydney. Then, in 2017, an additional female, Vanessa, was collected from Ball’s Pyramid to further increase the genetic diversity within the captive population.

The original greenhouses for breeding Lord Howe Island stick insects at Melbourne Zoo. The old-fashioned electrical equipment, partially hidden under the leaves, ensures sufficient humidity. Photo: Patrick Honan. Source: Return of the Phasmid, R. Wilkinson

After the collapse of the Sydney colony, it became clear that any catastrophic event affecting the only remaining captive population in Melbourne could wipe out all conservation efforts. This led to the idea of establishing additional breeding groups abroad. One of the first European institutions entrusted with the rare insects was Bristol Zoo Gardens in the United Kingdom. It was from Bristol that we received the eggs upon which Prague Zoo’s stick insect colony was established.

Today, there are more than a thousand Lord Howe Island stick insects in conservation breeding programmes, and the species is close to making a comeback to its original homeland. In 2019, a large-scale rat eradication programme was launched on Lord Howe Island, and conservationists are now monitoring whether rodents have truly been eliminated. So far, the results are promising.

Efforts to reintroduce the Lord Howe Island stick insect also include genetic research, which aims to determine the best breeding strategies to maintain maximum genetic diversity and the most effective approach to reintroduction. Prague Zoo has been significantly involved in this research for many years.

“Insects are often the drivers of an ecosystem just by their sheer numbers. If humans were to disappear from the earth, there are unlikely to be any negative effects. But if insects go, the entire environment collapses.”

– Patrick Honan

Invertebrate keeper Patrick Honan with his rare charges. Photo: Rod Morris, Zoos Victoria. Source: Return of the Phasmid, R. Wilkinson

The Lord Howe Island stick insect (Dryococelus australis) originally inhabited Lord Howe Island, lying in the Tasman Sea, at the southern edge of the Pacific Ocean, approximately 700 km northeast of Sydney. It is crescent-shaped, formed from an eroded volcano, and measures 12 km in length and 3 km in width.

After the discovery of the live Lord Howe Island stick insects on Ball’s Pyramid in 2001, it was decided to establish a conservation breeding programme for the species. Over the years, a total of five specimens were collected from the sea stack. Thanks to the dedication and immense efforts of conservation teams working to...

In the unique Ball’s Pyramid exhibit, you will see both the Lord Howe Island stick insects themselves, which were long considered an extinct species, and a scaled-down model of the rocky sea stack where they survived. Discover the story of faith, enthusiasm, and immense effort that has been put into saving a species that...

ZOOPRAHA.CZ

Contacts

- The Prague zoological garden

U Trojskeho zamku 120/3

171 00 Praha 7

Phone.: (+420) 296 112 230 (public relations department)

e-mail: zoopraha@zoopraha.cz

Others