A surprising ark: Ball’s Pyramid

For years, the Lord Howe Island stick insect was believed to be extinct. However, it turned out that it had survived in the most unexpected place of all: Ball’s Pyramid. The world’s tallest sea stack—a seemingly inhospitable shard of rock jutting out of the ocean like a giant pointed tooth.

Ball’s Pyramid. Photo: Miroslav Bobek, Prague Zoo

Ball’s Pyramid. Photo: Miroslav Bobek, Prague Zoo

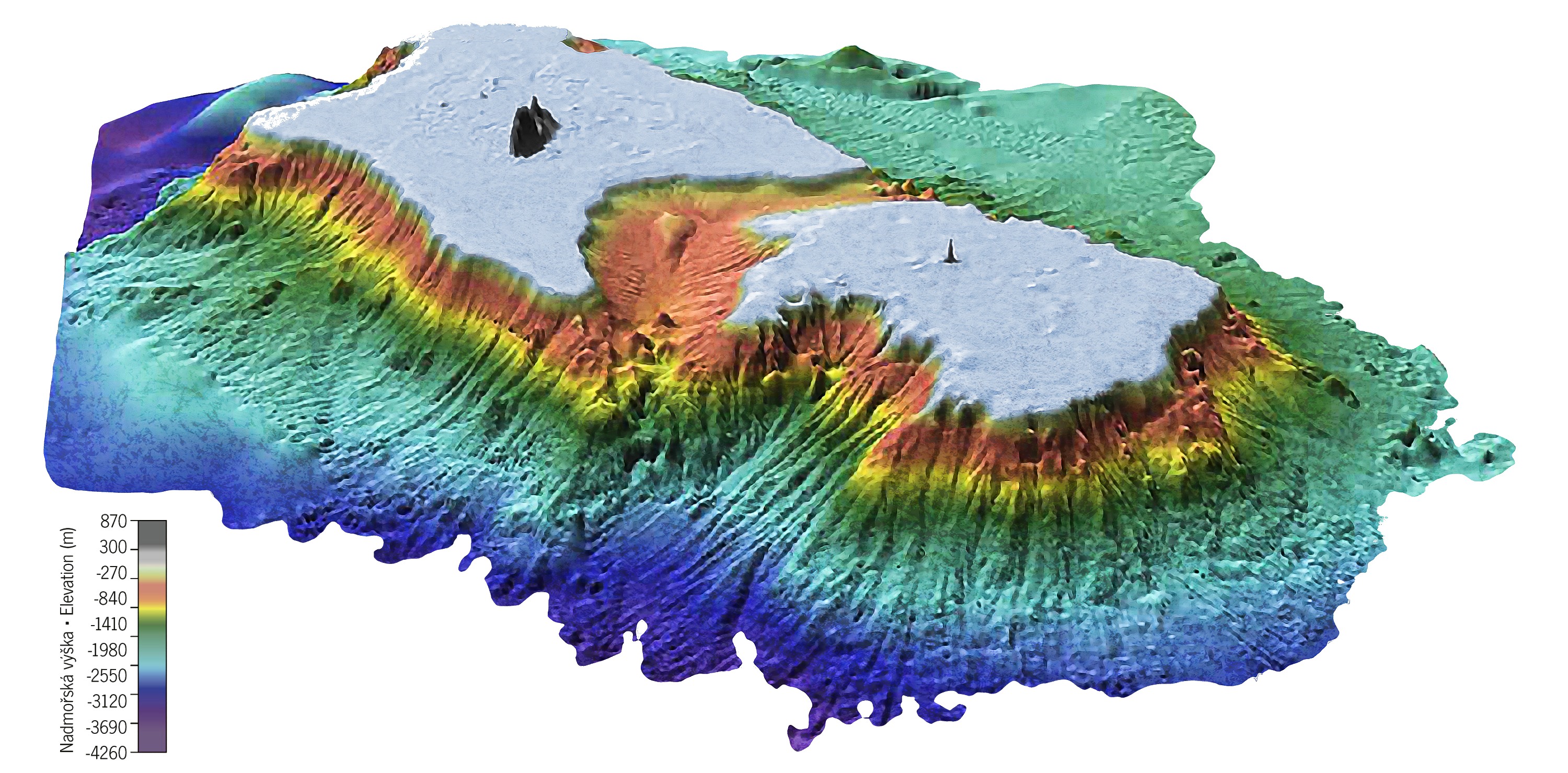

At 562 metres, Ball’s Pyramid is the tallest known sea stack on Earth. It is the remnant of a shield volcano’s vent, which was active 6.4 million years ago. Over time, erosion removed the softer rock layers, leaving behind a resistant basalt core—an islet measuring 1,100 metres in length and 300 metres in width. With its steep cliffs and isolated location, Ball’s Pyramid is one of the most dramatic sea stacks in the world. However, most of the former volcano remains hidden beneath the ocean’s surface. Below lies a vast underwater plateau, separated by an 800-metre-deep trench from the shelf that supports Lord Howe Island. The surrounding seafloor plunges into depths of up to three kilometres.

Bathymetric visualisation of the seafloor relief around Ball’s Pyramid (on the right) and Lord Howe Island (on the left). Source: Geoscience Australia

Outpost of adventurers

With its unique appearance and height of over half a kilometre, Ball’s Pyramid has long attracted climbers and adventurers. The first recorded attempt to reach the summit was made in 1923 by adventurer Logan Morrisby. In March 1964, Richard Higgins and David Roots unsuccessfully attempted to reach the summit. They returned to Ball’s Pyramid in the autumn of the same year, when geologist David Roots made an unprecedented discovery: fresh remains of the Lord Howe Island stick insect, supposedly extinct and unlikely to survive on the inhospitable rock.

The first evidence of the survival of the Lord Howe Island stick insect was documented in 1964 by David Roots, who discovered and photographed a newly deceased specimen while attempting to reach the summit of Ball’s Pyramid.

At the time, he had no idea of the significance of his unique discovery.

Source: Return of the Phasmid, R. Wilkinson

A few months later, on 16 February 1965, Bryden Allen became the first person in the world to reach the summit of Ball’s Pyramid. This was followed by numerous other expeditions, mostly climbing-related but also scientific. In 1969, during one of these expeditions, zoologist Jim Smith discovered other remains of dead stick insects. However, efforts to find live specimens and confirm a surviving population of Lord Howe Island phasmids on Ball’s Pyramid were unsuccessful.

In 1982, Ball’s Pyramid, along with Lord Howe Island, located 23 km away, was granted UNESCO World Heritage status, and a complete ban on access for private groups was introduced. However, in 1990, policies changed, allowing scientific expeditions with direct approval from the Minister for the Environment.

Despite strict entry regulations, a constant stream of applications flooded the government of the Australian state of New South Wales, under whose jurisdiction Ball’s Pyramid falls. Although none of the applicants were entomologists or at least trained natural scientists, the clause "for scientific purposes" became the key phrase in entry requests, with the search for the elusive Lord Howe Island stick insect cited as the primary reason for expeditions.

A pivotal decision

For nearly a decade, the government of New South Wales had consistently rejected requests to access Ball’s Pyramid. Eventually, it decided to settle the issue, once and for all, by organising its own scientific expedition to prove that the Lord Howe Island stick insect did not inhabit the isolated rock tower. Previous discoveries of dead remains had been attributed to birds, which were believed to have carried them there.

To everyone’s surprise, however, the expedition, led by David Priddel, made a remarkable discovery. During a challenging night-time climb in early February 2001, the team found three living specimens of the Lord Howe Island stick insect.

Members of David Priddel's expedition had to traverse a 300-metre stretch along the base of the island just above the waves before starting their ascent of Ball’s Pyramid. At times, the ledge narrowed to just a few centimetres...

Photo: Nicholas Carlile. Source: Return of the Phasmid, R. Wilkinson

After finding live stick insects on the Pyramid’s only green shrub of the Lord Howe Island tea tree, a race against time began. The fragile and extremely small habitat of the stick insects could easily have been threatened, and the insects themselves, as an extraordinarily rare species, could have fallen victim to reckless collectors or poachers. Over the following week, it was decided to establish a breeding programme on the Australian mainland with the goal of reintroducing the giant insect to its original homeland—Lord Howe Island.

Ball’s Pyramid stands as both a symbol of hope and a warning. The rediscovery of the Lord Howe Island stick insect proved that even supposedly extinct species can survive in the most improbable conditions. At the same time, it highlighted the fragility of ecosystems and the urgent need for their protection.

David Priddel and Margaret Humphrey, February 2001. Photo: Nicholas Carlile. Source: Return of the Phasmid, R. Wilkinson

The Lord Howe Island stick insect (Dryococelus australis) originally inhabited Lord Howe Island, lying in the Tasman Sea, at the southern edge of the Pacific Ocean, approximately 700 km northeast of Sydney. It is crescent-shaped, formed from an eroded volcano, and measures 12 km in length and 3 km in width.

After the discovery of the live Lord Howe Island stick insects on Ball’s Pyramid in 2001, it was decided to establish a conservation breeding programme for the species. Over the years, a total of five specimens were collected from the sea stack. Thanks to the dedication and immense efforts of conservation teams working to...

In the unique Ball’s Pyramid exhibit, you will see both the Lord Howe Island stick insects themselves, which were long considered an extinct species, and a scaled-down model of the rocky sea stack where they survived. Discover the story of faith, enthusiasm, and immense effort that has been put into saving a species that...

ZOOPRAHA.CZ

Contacts

- The Prague zoological garden

U Trojskeho zamku 120/3

171 00 Praha 7

Phone.: (+420) 296 112 230 (public relations department)

e-mail: zoopraha@zoopraha.cz

Others